Details

Article

I am a Mexican-American student who was born in a small American border town known as Nogales, Arizona, but raised on the Mexican side, Nogales, Sonora. Shortly after I was born, my mother’s visa to enter the United States (U.S.) expired. In turn, my parents decided to raise my older brother, Jim, and I in Mexico.

As a child in Sonora, I never understood why the two Nogaleses—known in Spanish as Ambos Nogales—split into two towns. After all, the people on both sides looked similar, spoke the same languages, and ate identical foods. Why was there a wall between them? Why did only people from Mexico need papeles (papers) to enter the U.S. and not the other way around?

I have vivid memories of crossing la frontera—the border—with my brother at dawn to attend elementary school in the U.S. While waiting in line, my grandmother, a tough, fair-skinned lady with short, golden-brown hair, always reminded us in Spanish, “You live with me. Remember your name and age.” One morning, an immigration officer pulled Jim and me aside for questioning. Jim, who was already in the second grade, understood English well enough to answer the uniformed man’s questions. I, on the other hand, only spoke Spanish. When he pointed at my grandma and asked me who she was, I froze. Frightened, I hid under my school’s maroon collared shirt and began to cry. I was only six years old.

As a child in Sonora, I never understood why the two Nogaleses—known in Spanish as Ambos Nogales—split into two towns. Why did only people from Mexico need papeles (papers) to enter the United States and not the other way around?

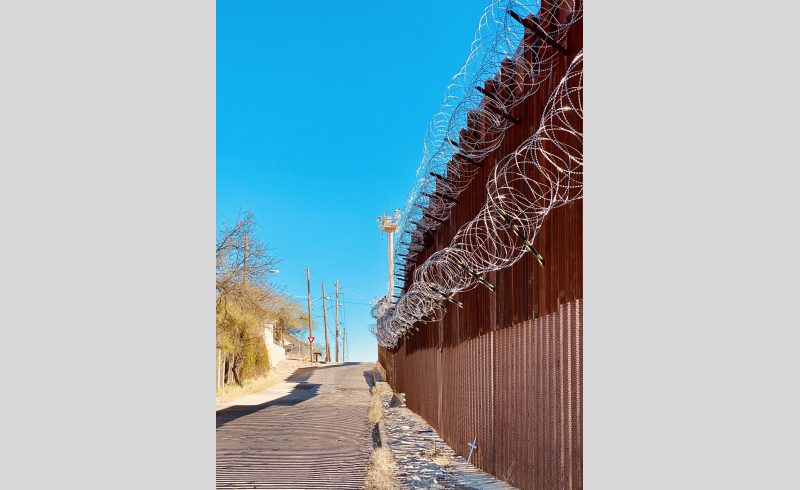

The border dividing Ambos Nogales looks significantly different today from la frontera I crossed as a child. Back then, it was normal for people to queue for a few minutes and answer a couple questions at the port of entry. Entering the U.S. was, for the most part, a simple process. Today, “normal” has become waiting for hours in line, answering copious questions, and submitting to arbitrary and unchecked inspections. The wall separating the U.S. and Mexico has also drastically changed; it has become more palpable. It is now a 20-foot-high concrete and steel fence enveloped in razor wire. The border consists of stadium-type lighting, fixed surveillance towers, cargo scanners, drug-sniffling dogs, thermal and infrared sensors, biometrics, and other security technologies, painting a toneless portrait of two countries at war.

La frontera has become one of the world’s most militarized borders. Yet, the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border is a recent phenomenon. In the mid-1970s, the U.S. deployed a “low-intensity conflict doctrine” (a military strategy used to control insurgent revolutionaries in Central America) along the southern border as part of the unsuccessful campaign in the “War on Drugs.” Various military instruments—helicopters, night-vision equipment, ground sensors—poured into the Southwest. Then, in the 1990s, the Clinton administration took extraordinary steps to address widespread anti-immigrant fervor. In addition to signing the most punitive immigration reform bill into law, President Clinton endorsed a border enforcement strategy called “Prevention Through Deterrence” (PTD) to stop undocumented migration. PTD, in short, augmented security in urban areas—like Ambos Nogales—in a deliberate attempt to funnel undocumented migrants into remote regions of the border, where crossing conditions are much tougher. PTD not only accelerated the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, but it also contributed to the deaths of more than 5,000 people in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona.

While waiting in line, my grandmother, a tough, fair-skinned lady with short, golden-brown hair, always reminded us in Spanish, “You live with me. Remember your name and age.”

In 2000, my mother, lacking papeles, could have become another death in the desert when we immigrated to Tucson, Arizona. Fortunately, she never had to make that perilous journey; she was smuggled through a drainage tunnel beneath the border. For years, she lived in the shadows of Tucson’s cityscape, selling food and cleaning motel rooms for a living. Then, on October 13, 2009, while applying for a green card, my mom was torn apart from our family and barred from returning to the U.S. for ten years. She was banished from the U.S. as a consequence of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, the punitive reform that President Clinton supported along with PTD.

The Clinton administration is neither solely responsible for the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border nor for the expansion of punitive immigration policies. President Clinton may have set the process in motion, but all three of his successors have participated to varying degrees in the construction of an ever-growing immigration enforcement machinery. We must not look beyond the U.S. Border Patrol’s annual budget to visualize this growth. In 1990, for example, their budget was $262,647. In 2019, the U.S. spent nearly $4 billion on border enforcement.

According to the International Organization for Migration, the international migrant population increased from 84 million in 1970 to nearly 244 million in 2015—a great portion of which occurred from developing regions to more industrialized countries in the Global North.

At the same time, however, the U.S. is not unique in fortifying its borders and struggling with pervasive anti-immigrant sentiments. Western liberal democracies in North America, Europe, and Australasia are wrestling with the forces of increased globalization. The rapid flux of political, economic, and technological exchanges at the end of the millennium have facilitated global integration, and in the process, escalated the movement of people. According to the International Organization for Migration, the international migrant population increased from 84 million in 1970 to nearly 244 million in 2015—a great portion of which occurred from developing regions to more industrialized countries in the Global North.

In response to these changes, Western liberal democracies—the United Kingdom, Greece, Italy, Australia, and others—have relied on border enforcement measures and strict immigration policies to manage and control mobility in a globalized era. By and large, immigration enforcement has disproportionately affected people from ethnic and racial minority backgrounds.

There is no question regarding whom U.S. immigration enforcement has overwhelmingly controlled. The Latino community has suffered the burdens of mass deportation, family separation, and the expanding criminalization of immigration. This includes locking migrant children in cages and enacting groundless rules for excluding asylum seekers and limiting legal immigration. Today, the infliction of pain and suffering as a means of excluding Latinos has become an everyday feature in U.S. immigration law; it has become the new “normal.”

While la frontera has changed, Ambos Nogales stand stronger than ever. “Juntos por amor a Nogales”—“United by the love of Nogales”—is the town motto of Nogales, Sonora. Separated by a border, but united by love, my family also remains strong.

Looking back at my childhood, I never imagined that my life would revolve around crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. My mother returned to Nogales, Sonora when the U.S. banished her for ten years. Over the past decade, she has been living a block away from where she raised me in Mexico. My siblings (three of them now) and I have visited her as often as possible. While la frontera has changed, Ambos Nogales stand stronger than ever. “Juntos por amor a Nogales”—“United by the love of Nogales”—is the town motto of Nogales, Sonora. Separated by a border, but united by love, my family also remains strong.