Details

Article

For one thousand years, Jews called Poland home. And for one month last summer I ventured back to the country my great-grandparents fled, following the lines of the Warsaw ghetto wall, hoping to rediscover some remnants of home.

I was in Poland as a Humanity in Action fellow, studying the rise in hate speech while promoting equitable conversations on human rights. I was assigned to work with the Polish non-profit Forum Dialogu (Forum for Dialogue), where I developed interactive maps of the Jewish history of towns and villages throughout the country. These maps are based on walking tours planned by children to educate suburban and rural communities on the rich Jewish populations that once resided in their towns. Designing these maps granted me much-needed optimism during some of the harder days.

I had worn my kippa outside daily, against the wishes of my family and the advisement of members of Ec Chaim, the Reform congregation of Warsaw. Most days it was just some stares. On occasion there were comments, antisemitic gestures or nazi salutes. I was followed more than once through streets and in bars— some of which I told friends and family about, others I kept in so as not to worry anyone.

Most days it was just some stares. On occasion there were comments, antisemitic gestures or nazi salutes. I was followed more than once through streets and in bars— some of which I told friends and family about, others I kept in so as not to worry anyone.

When I first arrived, I had tried my best to prepare for these moments. I asked Polish friends to warn me about any derogatory words I might hear in the streets. One friend confessed, “I won’t even say the word Żyd [Jew].I think that’s the worst thing to get called here.”

“I won’t even say the word Żyd [Jew]. I think that’s the worst thing to get called here.”

I felt visible, but in all the wrong ways. I could have sworn I was the last living Jew in a nation of ghosts. The words of Polish-born Jewish philosopher, Simon Rawidowicz, followed me throughout my month in Warsaw. “He who studies history will readily discover that there was hardly a generation in the diaspora that did not consider itself the final link in Israel’s chain… each generation grieved not only for itself but also for the great past that was going to disappear forever, as well as for the future of unborn generations who would never see the light of day.”

On my penultimate night in Warsaw, I presented an interactive map I designed with two Polish activists, Beata Janus and Dominika Kaszewska, who also worked with Forum for Dialogue. We created a Jewish historical walking tour of Warsaw’s Praga district. At one point, Jews made up nearly half the population of Praga. The central stop of the tour was an old Jewish flour mill that produced matzah up until the Nazis invaded Poland. During the war, mill workers smuggled flour into the Warsaw ghetto to feed the starving masses. Today, the mill is a pile of rubble surrounded by crumbling brick walls.

After our presentation, the three of us embarked on our own tour. We snuck into the site of the old mill. Dominika had told me about an artist, Rafał Betlejewski, who had spray painted “Tęsknię za tobą, Żydzie” (I miss you, Jew) on the wall of this site. This was just one piece of a much larger mural series. The message was promptly covered over by authorities, and Betlejewski was charged.

Standing before this blotted-out message, I was overcome by emotion. It was the only indication that this pile of rubble was holy ground for people like me. I felt obliged to respond. I turned to Dominika and asked if she wanted to break the law with me. She said yes.

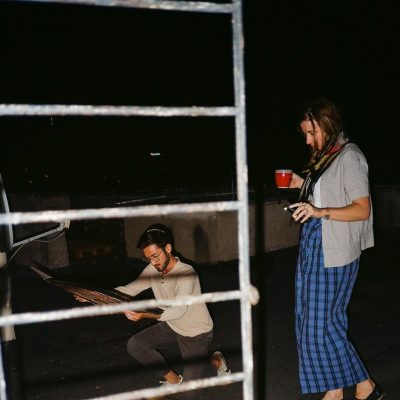

I returned to the old mill late the next night, donning my kippa and clutching a can of spray paint. Dominika monitored the entrance as my jittery hand spray painted “Mir Zaynen Doh” onto the crumbling facade. “Mir Zaynen Doh” (We Are Here) is the final line of the Yiddish song “Zog Nit Keyn Mol”, a Holocaust memorial anthem sung around the world. I had grown up singing it at my Jewish union-activist summer camp. It was sung by my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents.

The police appeared outside the mill and we left through the back. As we turned our first corner, a man stopped me on the street and gestured toward his head, referring to my kippa. I was prepared for my big cathartic moment to be diminished by another antisemitic comment. He made a remark in Polish, smiled, and went on his way. Confused, I turned to Dominika for an explanation. “He said, ‘it’s nice to see you wearing that.’”

Rawidowcz wrote, “We, the last Jews! But if we are the last—let us be the last as our fathers and forefathers were. Let us prepare the ground for the last Jews who will come after us, and for the last Jews who will rise after them, and so on until the end of days.”

I didn’t find any real remnants of home in Poland; but I tried to prepare the ground for those who come after me, hoping to rediscover home in this nation. Dominika assured me that she would paint “We Are Here” on walls all across Poland.

I didn’t find any real remnants of home in Poland; but I tried to prepare the ground for those who come after me, hoping to rediscover home in this nation. Dominika assured me that she would paint “We Are Here” on walls all across Poland.

I have prayed over the mass grave of seven hundred children murdered in the woods of Krakow, the town my great-grandfather grew up in. I have buried fragments of bones that still sit above the surface in Majdanek, the first Nazi camp to be liberated. I stood in the cattle cars that transported Jews to their deaths, and I stood in the gas chambers. And yet, I left Warsaw feeling more alive than ever before.

If we are the last living Jews in a nation of ghosts, let us embrace this life we were given. Let us rejoice fully in our tradition, as if we were the final link of this chain. Let them know that we are here— that we lived to tell our story.

Jacob Fertig, 2019