Details

Article

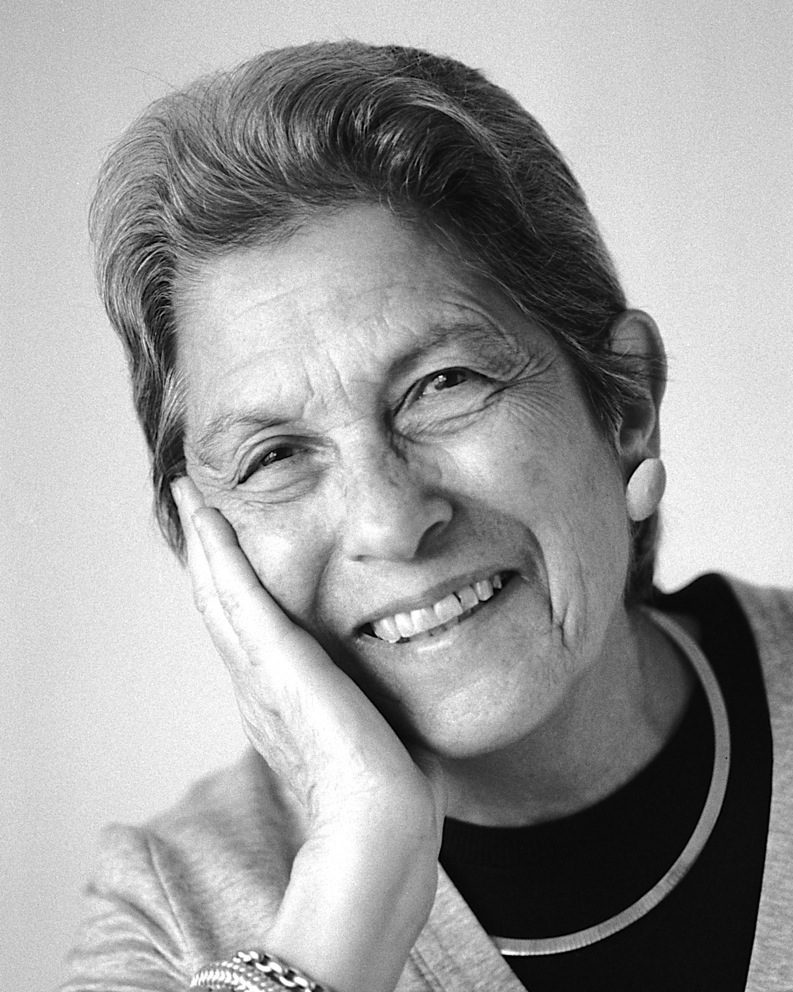

This note was written by our founder, Dr. Judith Goldstein, to Senior Fellows and Fellows.

The Week Before the Election

In the midst of these past months of anguish, John Robert Lewis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg died. The news was shocking despite the fact that we knew that each one was fighting advanced pancreatic cancer. Lewis passed in July, Ginsberg in September. In their final days each one was acutely aware of the political stakes of the 2020 presidential election. Both incited the ire of the President well before their deaths. Ever vigilant, they left parting words to accompany their legacies of determination and courage to make their country ever more just. “Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble,” Lewis wrote in an article that he asked the NY Times to publish the day of his funeral. “Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it.” (Lewis, John. “Together, You Can Redeem the Soul of Our Nation.” NY Times, 30 July 2020). Ginsburg’s parting message to the public, which, according to her granddaughter, was that she would not be replaced until a new President was installed. (“Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s ‘most fervent wish.” BBC, 21 September 2020)

The funerals gave pause to the political madness enveloping the country in the course of the 2020 presidential election. In lauding Lewis, Rev. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock told mourners at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church that “time stood still while the nation takes its time to remember him”–to remember the greatness of the Civil Right leader. The same was true for Ginsburg as the public, over many days, extolled her profound work. The tributes, imbued with historical significance, invoked the moral, political and spiritual depths of an aspirational America. The memorial services for Lewis and Ginsburg were replete with religious references. The Reverend reminded the country that at age 16, Lewis thought of becoming a minister but he turned another way. “Instead of preaching sermons,” Rev. Warnok said of Lewis “he became a living, walking sermon about truth telling and justice making.” (“Funeral for Congressman John Lewis.” Transcripts CNN, 30 July 2020. Video here). In Washington at the ceremony inside the Supreme Court, Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt spoke about Justice Ginsburg, with words that belong to Lewis, as well from the Judaic tradition, liturgy and laws. “To be born into a world that does not see you, that does not believe in your potential … and despite this, to be able to see beyond the world you are in, to imagine that something can be different: that is the job of a prophet. And it is the rare prophet who not only imagines a new world but also makes that world a reality in her lifetime.” (Zauzmer, Julie. “‘Blessed is God, the true judge’: Ginsburg memorialized in Hebrew in the Halls of the Supreme Court.” The Washington Post, 23 Sep. 2020).

From vastly different backgrounds of deprivation, Lewis and Ginsburg built long careers that brought them to the epicenter of politics and the law in Washington. In their 80s, Lewis and Ginsburg were elders, vibrant models who had led battles that brought both epochal victories and searing defeats in realizing the promises of American democracy.

From vastly different backgrounds of deprivation, Lewis and Ginsburg built long careers that brought them to the epicenter of politics and the law in Washington. They gained deep respect in the House of Representatives and the Supreme Court. In their 80s, Lewis and Ginsburg were elders, vibrant models who had led battles that brought both epochal victories and searing defeats in realizing the promises of American democracy. Lewis was a child of the Jim Crow South whose family endured generations of slavery followed by sham citizenship, deficient education, poverty and violence. Ginsburg’s Jewish family, new to America in the early 1900s, left Eastern Europe to escape centuries of religious intolerance and bedlam. When asked about the difference between being the daughter of a bookkeeper in Brooklyn and a Justice on the Supreme Court, RBG quipped: “one generation.” But there was much more to that amazing transformation than she implied. Her family, along with millions of other Jews, came from an insular world held together by their religion and culture in Eastern European countries that allowed few opportunities for Jews to thrive. Immigrant Jews, desperate, poor and on the run from violence and suffocating prospects in Europe, believed they were entering the American land of secular liberation. In fact, her family entered a country that was steeped in Christian-bred residential, educational and commercial segregation aimed at Jews. Restrictions were based on racial hierarchies, practiced most egregiously through Jim Crow laws in the South and through prejudice in the North and West.

Ginsburg’s family came to a country that in theory had no state religion and would provide equal opportunities for all, but the reality was vastly different, especially for Blacks and Native Americans. Ginsburg’s “one generation” quip could hardly apply to them. Theirs was a centuries-long history trapped in a white Christian culture of legal and/or de facto slavery, followed by iron clad mechanisms of exclusion and racial hierarchy. Despite oppressive forces, Blacks held firmly to promises of redemption, based in sacred Christian beliefs and the secular American value of equality. Lewis based his life on both. Unlike his mentor Martin Luther King Jr., Lewis moved on to the secular battleground. The great grandson of slaves, his life would be one of activism and soaring oratory—to break down the legal structures of inequity as embedded in state and federal laws and practices.

The great grandson of slaves, his life would be one of activism and soaring oratory—to break down the legal structures of inequity as embedded in state and federal laws and practices.

Both Lewis and Ginsburg were part of a generation that grew to maturity in the post-Depression, post-World War II, post Holocaust and decolonizing years. America surged to power, with unprecedented wealth, strong communal organizations and an infatuation with its image as the world’s leading democratic state despite the reality of Jim Crow. “The story of the American experiment in the twentieth century is one of a long upswing toward increasing solidarity, followed by a steep downturn into increasing individualism. From ‘I’ to ‘we’ and back again to ‘I’.” This conclusion is at the heart of Robert D. Putnam’s and Shaylyn Romney Garret’s recent publication The Upswing (Brooks, David. “How to Actually Make America Great.” NY Times, 15 Oct. 2020). The 1940s to 1960s, the years in which Lewis and Ginsburg developed their passions, were ones of an expanding sense of “solidarity”—of individual possibilities and determination. That solidarity, evident in the mid-40s to early 60s, was partially based on the exclusion of Blacks from the democratic system, the respite from immigration of so-called undesirable nations since restrictive legislation passed in 1924, and the seeming success of the American melting pot.

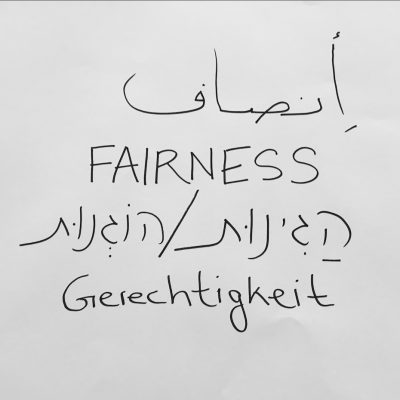

This was the time, from the 60s on, that Ginsburg and Lewis dedicated themselves to making America accountable for its democratic deficiencies, particularly in regard to Blacks and women—to make democracy work. There was so much that was wrong. They plunged into the fight to expand the rights of citizens—to attain equal and full rights particularly on gender and racial issues. Lewis courageously took action, at the price of horrific physical abuse, in buses, restaurants, streets and highways in the South as part of the Civil Rights campaign; Ginsberg in countless briefs in the courts and articles in the legal academy to gain equal rights and reduce inequitable gender differences—differences, as she recognized, that impinged on men as well. Over decades, they did their work, one in making laws, the other in rendering interpretations. Lewis and Ginsburg were guided by and beholden to the Constitution as the bedrock of their mission and ideals. Jeffrey Rosen, a friend of the Justice and legal critic of the Supreme Court stated that RBG “has become one of the most inspiring American icons of our time and is now recognized as one of the most influential figures for constitutional change in American history.” (Rosen, Jeffrey. RBG: Conversations with Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Life, Love, Liberty and Law, Henry Holt and Company, 2019, kindle edition 6) When Lewis was once asked to account for his march from poverty and desperation in Alabama to outstanding service in the House of Representatives, he answered in four words: belief in the Constitution.

Both had their critics. Many feminists thought Ginsburg too conservative, especially in her criticism of Roe v. Wade. And many Blacks thought Lewis too attached to pursuing incremental change through the political process. The public, however grew to revere Lewis and Ginsburg and convert them into heroic models for children and adults. Their images became memes, their portraits subject to artistic hagiography and adoring caricatures. Ginsburg assumed a near cult status when she became RBG after her dissent in the voting rights case Shelby County v. Holder 2013, a landmark case that threw voting rights for Blacks into retreat. Suddenly, RBG images adorned clothing, bags, books for children and wherever her picture could adorn an object. In downtown Atlanta wall painted images of Lewis rivaled in popularity the ones that filled the graphic rendition of his memoir Walking in the Wind.

John Lewis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg spent their lives defining and expanding what “equality should mean.” We need to follow them in this time of stress and instability as the democracy—the one they fought so hard for, is tested once again.

“Our history to the present day,” the novelist Marilynne Robinson wrote, “is proof that people find justice hard to reach and to sustain. It is also proof that where justice is defined as equality, a thing never to be assumed, justice enlarges its own definition, pushing its margins in light of a better understanding of what equality should mean.” John Lewis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg spent their lives defining and expanding what “equality should mean.” (Robinson, Marilynne. “Don’t Give Up on America.” NY Times, 9 Oct. 2020). We need to follow them in this time of stress and instability as the democracy—the one they fought so hard for, is tested once again.