Details

Article

From July 1-3, Humanity in Action held its 10th International Conference, as part of the wider project, Untold Stories | Forgotten Places. Over 100 participants came together, focusing on antisemitism, racism, discrimination and hatred towards the LGBTQI+ community in Europe, with an aim to advance an inclusive and diverse culture of remembrance.

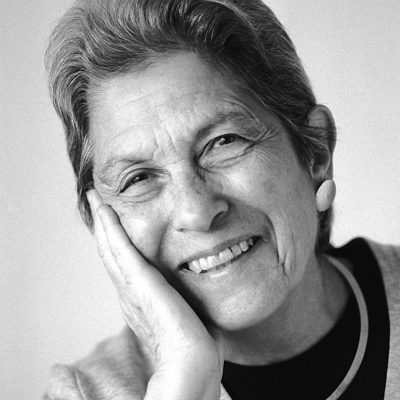

At the conference, Humanity in Action Executive Director Judith Goldstein gave introductory remarks to conference participants, in which she offers new sources to provide additional perspectives on some unknown stories and landscapes of the past. Executive Director Goldstein’s remarks are below, in full:

A few months ago, the wise and prolific Israeli author A.B. Yehoshua was the subject of a film documentary The Last Chapter of A.B. Yehoshua. An outspoken critic of the settlements, at 85 years he was old, sick, depressed and lonely since the death of his beloved wife – in fact just a few months away from dying. As he sat by the Mediterranean Sea, he threw his comments, looking away from the camera, at the water: “We should forget more. We should forget so that we can make room for new things in our mind. All that rummaging in our mind through the past, with the past is paralyzing. And then everyone in Israel – Arabs and Jews – should get dementia.”

If we put aside dementia as a dark joke about the ongoing tragic conflict, we might consider what he said as a mix of right and wrong – or what to accept or dismiss. It would be wise to follow his words, but not completely. Let me twist them a bit since there is so much to think about following his thoughts. He is speaking about obsessions with the past, being stuck in the past, fixated and frozen in old ideas, knowledge, feelings and habits. He wants to clear the mind to think new thoughts. In fact, he implies that it is only by clearing the mind that new thoughts can emerge.

True but not true! In fact, one can profitably probe the past for truth to clear the individual mind and society’s collective mind for new thoughts and ways of living. The task is invaluable, necessary and immensely difficult.

That is what so many of you have been doing for the past months. At the behest of Humanity in Action and the EVZ foundation, Untold Stories | Forgotten Places challenges us to explore landscapes of historical inquiry. What an opportunity, provided by EVA, to think anew as many of you have taken on the task of research in the field. My admiration to you all. I, on the other hand, am avoiding your hard work to take a shortcut in thinking about “Untold Stories.” As an historian, I am relying on other historians to lead the way into unknown stories of Holocaust, racism and LBGTQ history. Fortunately, I can turn to two books, published this past year, one article and one talk that present significant contributions to the study of racism and LBGTQ history. These are mostly American inquiries but important beyond our borders. I am sure that there are many other recent significant European studies on these issues that I have not read.

The publication The 1619 Project provides a compilation of historical and contemporary essays about Black Americans – locked out of the benefits of American freedom, citizenship, health and wealth; locked into slavery, segregation, discrimination, poverty and deliberately poor medical support. Nicole Hannah-Jones, the “creator” of the book, has identified categories of inequality and vulnerability. They are innumerable, staggering in ingenious vicious intent and numbing in their reach and longevity. 1619 was the year that the first Black people were brought to Virginia and bound into slavery. The chapter headings tell the historical and contemporary histories and repercussions: “Democracy,” “Race,” “Sugar,” “Fear,” “Dispossession,” “Capitalism,” “Politics,” “Citizenship,” “Self-Defense”, “Punishment,” “Inheritance,” “Medicine,” “Music,” “Healthcare,” “Traffic,” “Progress,” and “Justice.” Cumulatively, there are thousands of examples of brutality, the denial of democracy, the rule of law and violations of human rights. In the essays there are thousands of examples, as well, of Black religious faith and cultural resistance created in the hope to be set free and given assets and dignity as part of the American promise.

The 1619 Project first appeared as a long essay in the New York Times. It was a powerful, unapologetic call for Black inclusion and accuracy in constructing the American story. The article was received with appreciation and relief in many quarters but heatedly contested and denigrated in others. Accepted as curriculum in many schools, banned from others. It shoots right at the target of understanding fully the dynamics of American history and contemporary life. The title challenges the founding myth of an American revolutionary concept of democracy: gloriously white, religiously inspired, solidly based in western European, Enlightenment traditions and thought. The year 1619 is a refutation: designated by the authors as the founding moment of American life when the first Black people were forced on American soil as slaves. A refutation of the single, authentic, God-inspired founding myth of European colonial settlers and the 1776 Declaration of Independence to justify ending British rule. 1619 was the moment when the system of exclusion and deprivation poisoned the hope of freedom and democracy—the great American experiment of exceptionalism—for Black people, in particular, and America as a whole.

1619 presents multiple unknown stories, on an immense scale, constituting a reworking of American history. It is powerful and deeply significant in the canon of American historical writing and truth telling—in recognizing that Black people have been caught in the “undertow of American reality,” in the words of Carol Anderson. Or almost truth telling in its singular focus in restorative history in bringing Black history to its rightful place! 1619 is part of a potent campaign to overturn ignorance and exclusion. It is not, however, a full multi-dimensional history of America. It was not intended to do that job. It is, in fact, an ideological work of critical importance to develop, finally, an accurate, complete and truly integrated American history.

Unknown stories of LBGTQ history have been amplified by two recent American publications: Jamie Kirchick’s Secret City and a recent article, “Behind the Blood Ban: Donor Discrimination has Deep Roots” by Jacob Fertig, a Senior Fellow. Kirchick’s book, an exhaustive study of a particular history exposes discrimination, mainly from the 1930s to the late 1990s, against homosexuals in American government and politics. By law and societal practice, homosexuals were forced to hide their sexual lives and identifies. In the closet, they were ever subject to exposure, loss of a career and criminal punishment. Washington’s straight white world sought to “out” homosexuals in the CIA, Treasury, State Department and other sites of power. Homosexuals, it was thought, were potential – or confirmed – agents of deceit and treason. Kirchick documents cases when careers of high officials were cut short and broken. Exposure was toxic. Families upended. When the stories broke, the press covered them as sensational exposures confirming America’s weaknesses in the Cold War. Consistent with the need to hide, the histories were locked away and ignored by many historians. Until now.

Fertig’s article brings together issues of LBGTQ people and the Holocaust. The article focuses on serology and blood issues, as they pertain to homosexuality, antisemitism and America’s racially imposed segregation. The starting point of the article is the current three-month restriction blocking homosexuals from donating blood for needy patients. The precedent goes back to the 1980s AIDS crisis when homosexuals were banned, under all circumstances, from donating blood. Fear of spreading the disease justified the prohibition. Fertig, however, takes the history even further back to Germany at the beginning of the 20th Century. Jews, he writes, were considered dangerous in part because of the idea that “identity is rooted in physical blood.” “Scientific antisemitism,” he wrote, “took center stage, thanks to a strong foundation of Christian antisemitism and the popular belief that medicine was independent from politics, religion, and ethics, and therefore a fairer basis for discrimination.”

Fertig cites a 1935 case when Dr. Hans Serelman, a German Jewish doctor was sent to a concentration camp for “race defilement.” He had given blood to a non-Jewish soldier to prevent him from dying. In the trial, Dr. Serelman “admitted to previously transfusing his own blood to save the lives of other patients when no other blood was available.” In every instance, Fertig concludes, “Serelman’s blood recipients survived because of his scientifically safe but socially risky actions.”

The same blood prohibitions and fears, Fertig writes, were part of the American enforcement of racial purity. Dr. Charles R. Drew was a Black American doctor and pioneer in preserving plasma as well as initiating blood banks in Great Britain during World War II. After returning to the States to work with the Red Cross and advance blood treatments, he withdrew when the organization refused to take blood from Black people. The official Red Cross position prohibited mixing races through blood: “For reasons which are not biologically convincing but which are commonly recognized as psychologically important in America, it is not deemed advisable to collect and mix Caucasian and Negro blood indiscriminately for later administration to members of the military forces.”

Drew castigated the decision: “I think the Army made a grievous mistake, a stupid error in first issuing an order to the effect that blood for the Army should not be received from Negroes. It was a bad mistake for 3 reasons: (1) No official department of the Federal Government should willfully humiliate its citizens; (2) There is no scientific basis for the order; and (3) They need the blood.” https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/community/articles/behind-the-blood-ban

And finally, I want to turn to one book by Konstanty Gebert that I wish I could read. It is written in Polish and therefore an insurmountable problem for me. In Gebert’s most recent talk with the 2022 Fellows, he described his study as his attempt to insist on precise definitions–especially in regard to the war in Ukraine. It is not a genocide now, he believes, but could be one int he future. Not every horrific war, despite the degree of destruction, is a genocide, he declared. To qualify, there must be a concerted and thorough effort to destroy a group that is considered threatening to the viability of a state or people.

Over centuries there were massacres and savagery but not until the modern era of national states did we humans develop the ideologically driven justification to cleanse a society of one group. In numerous European countries and America, religious, racial, and some gender groups were deemed diseased. Germany, to justify the need for Aryan purity and territorial gains, targeted Jews, homosexuals, Roma, and those with mental and physical disabilities within German boarders and the many countries that Germany occupied. Thus, devastation, the Shoah and the near eradication of a people.

Referring back to Yehoshua’s desire for new thoughts, let me suggest that 1619, The Secret State, “Behind the Blood Ban,” and Gebert’s talk provide entry into unknown stories and landscapes to find new perspectives on the past. I am grateful for the authors who do the hard work, especially now when it is so important that we face destructive uncertainties and tensions in our societies. So much is contested, if not in one place then another. Immediate issues of racial division in America are now serving as tools to block a more fully realized American democracy. European nations resist immigration to prevent increased diversity. dangerous to that nation. Regarded as dangerous to society, the Polish government targets homosexuals as unwanted and denies the rights of women to abortion. America as well. The country seemed to have finally integrated homosexuals into its society. Once again, however, powerful political and religious groups are pressing to retract an expanded social contract of inclusive marriage. The Texas Republican Party recently adopted a platform that castigates homosexuality as “an abnormal lifestyle choice.”

And the moral responsibility for the Holocaust is diminished in many places as new and old antisemitic tropes circulate openly in various countries. Your work puts you on the front lines in resisting these forces in unison with these authors. We can only hope that you will continue this important work.