Article

Every year, passport rankings dominate global headlines:

Every year, passport rankings dominate global headlines:

“The world’s most powerful passport.”

“Who climbed, who fell, and why.”

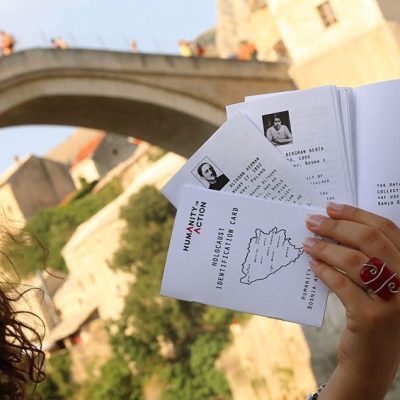

But what if that headline is only telling half the story? The project by Jasmin Hasić, Humanity in Action Senior Fellow (Berlin 2009) introduces the Spatial Passport Strength Index (SPSI), a new way of thinking about global mobility that asks a different question. Instead of focusing on how many countries a passport unlocks, SPSI asks: how much of the world’s physical space does that access actually cover?

From country counts to spatial reach

Traditional passport indexes treat all destinations as equal units. A visa-free entry to Luxembourg counts the same as visa-free entry to Canada, Brazil, or Australia. SPSI challenges that assumption by shifting the unit of analysis from states to space.

Using land area as a neutral proxy, SPSI measures the geographic extent of legal access a passport provides. The result is not a replacement for existing indexes, but a complementary perspective, one that reveals hidden structures in global mobility that country-count rankings tend to obscure. Some passports offer broad access to many small jurisdictions. Others grant entry to fewer countries, but across vast territorial spaces. SPSI makes that difference visible.

What SPSI does and what it doesn’t

SPSI is intentionally modest in its claims and explicit about its limits. It measures legal geographic access, not quality of life, desirability, or political values.

Land area is used as a descriptive, non-normative proxy for spatial extent not as a claim that all land is equally valuable. The index does not evaluate regimes or endorse destinations. Geography is not judgment.

Population and land area capture different dimensions of mobility. SPSI isolates spatial reach while leaving population-weighted extensions for future work. Internal freedom of movement is not measured, a limitation acknowledged and explored as a direction for refinement. The goal is not to crown a new “best passport,” but to show that mobility has different dimensions and that those dimensions don’t always align.

Why this matters

In an increasingly interconnected yet uneven world, mobility is often discussed as a simple hierarchy. SPSI suggests a more nuanced picture. It shows how breadth and depth of access diverge, how rankings shift when space is taken seriously, and how seemingly minor visa changes can reshape global mobility in spatial terms.

This perspective opens new questions for policymakers, researchers, and the public alike:

What kind of mobility does a passport actually enable?

How does spatial access shape economic, social, and strategic possibilities?

What do we miss when mobility is reduced to a single number?

An open, evolving research project

SPSI is presented as a working methodology, not a finished verdict. The project actively invites critique, alternative formulations, and methodological challenges from geographers, migration scholars, policy analysts, and data scientists. Substantive feedback will be acknowledged and incorporated where appropriate in future iterations. The aim is constructive engagement, not orthodoxy. SPSI doesn’t ask who has the strongest passport. It asks what kinds of mobility different passports make possible.

Download the working paper below.