Details

Article

The report on “Policing” was produced as a part of the publication: The Kerner Report: 50 Years Later. This publication was released by the 2018 Humanity in Action Detroit Fellowship program.

Part I: Introduction

“If we were to look at the larger-scale riots that we know of in our recent history—from Rodney King, to the Detroit riot in 1967, the Newark riot in 1967, Harlem riot in 1964, Watts in 1965—every single one of those riots was a result of police brutality. That is the common thread.” (1)

– Jelani Cobb, 13th

According to the Kerner Commission, the relationship between marginalized communities and the police was characterized by tension. “The atmosphere of hostility and cynicism,” the Commission wrote, “is reinforced by a widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a ‘double standard’ of justice and protection—one for Negroes and one for whites.” (2) This passive language treats ‘brutality’ as mere speculation, ignoring Detroit’s history of police terror. (3,4)

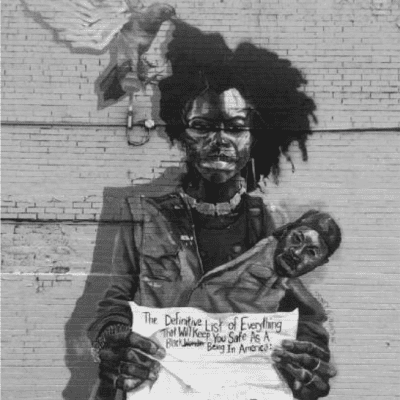

Fifty years later, we want to be direct. The racialized violences of police brutality are not a widespread “belief,” but an oppressive reality. Black Detroiters have lived this reality. After 1967, the Black community cited as the number one cause of the Rebellion. (5) Therefore, analyses of criminal justice policy must look simultaneously back toward the police’s white supremacist history and forward toward an accelerating carceral state.

At the time of the Rebellion, the DPD was what it had always been: an occupying force, whose duty to “protect and serve” never applied to communities of color.

The Colonialist Legacy of Policing

In the 1700s, colonizing Europeans feared African resistance to slavery and created slave patrols, paddy wagons, and militias to suppress rebellions and protect the interests of slaveholders. (6) In the 1830s, when the Underground Railroad ran through Michigan, Detroit’s City Council approved a 16-man patrol to catch escaped slaves. (7) This legacy persists: Detroit’s Police Department (DPD) was institutionalized after a 1863 race rebellion; the Detroit police murdered 55 African Americans in 1925 alone; “Big Four” terror squads routinely harassed Black Detroiters in the 60s. (8) By 1967, the Detroit police were 95% white in a 40% Black city. (9) Which means that, at the time of the Rebellion, the DPD was what it had always been: an occupying force, whose duty to “protect and serve” never applied to communities of color.

The Emergence of Mass Incarceration

Although the racial demographics of the DPD changed when Mayor Coleman Young enforced residency requirements for police officers, mass incarceration complicated the landscape of policing in the city. (10) Within months of releasing the Kerner Commission Report, Lyndon B. Johnson created the Office of Law Enforcement Assistance (OLEA), which funded a rapidly growing carceral state.(11) As white flight increased and city tax revenue decreased, Detroit falsified crime data to receive OLEA money. (12) The city hired law enforcement, purchased military equipment, and trained correctional officers (13) The state built 52 prisons. (14) Michigan’s incarcerated population increased by 538% (Figure 1).(15) Today, the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) disproportionately incarcerates Black Michiganders (49%) (16) and Wayne County communities (30%). (17)

Overview

This chapter describes how policies and practices—including racial profiling, pre-trial detention, employment discrimination, and body- worn cameras—impact Detroiters’ entrance into and departure from the state’s criminal justice system. We pay particular attention to the intersection between carceral and mental health systems, highlighting how racialized policy criminalizes and stigmatizes marginalized communities in Detroit.

Part II: Analysis

“The communities in which Black people live become occupied territories, and Black people have become seen as enemy combatants, who don’t have any rights, and who can be stopped and frisked and arrested and detained and questioned and killed with impunity.” (19)

– Melina Abdullah, 13th

Entry

Entry into the criminal justice system, dead or alive, is almost a rite of passage into (premature) adulthood for Black Detroiters. Police presence—and, with it, use of excessive force and practices of racial profiling—is widespread. Given Detroit’s proximity to the Canadian border and the predominantly Arab American community of Dearborn, the region has an unusually large number of FBI and ICE agents, in addition to city, state, university, campus, and drug enforcement police forces. (20) In 2000, Detroit’s rate of fatal police shootings was the highest in the nation. (21) A 2004 study found that Black drivers are 79% more likely to be stopped, cited, searched, and arrested than white people. (22) Public perception of racial profiling amongst Detroiters captures these dynamics well: in response to the Detroit Metropolitan Area Communities Study (DMAC)’s 2017 survey, only 1% of Detroiters believe that police are “more likely to use deadly force against a white person” compared to 52% that believe it would be the case for Black people (Figure 2). (23)

The forensic psychiatry system—or lack thereof—contributes to the criminalization of marginalized people, creating not only criminals, but repeat offenders. While Michigan once had 16 psychiatric institutions, this number has dwindled to 5. (25) These institutions were closed due to malpractice, but reform instead of total shutdown was necessary: people with mental illness did not just stop being ill once institutions closed. Many became homeless and re-entered the prison system systematically more than any other group of people in the nation; 25-50% of homeless people have a history of incarceration. (26) This major intersection between race, mental health, and class is often ignored.

“There is no mental health ‘system’ in Michigan…”

After closing three-quarters of Michigan’s psychiatric institutions, Governor John Engler was supposed to create community-based outpatient programs. Decades later, these programs have still not materialized. (27) As Tom Watkins, former Director of the now- inoperative State Mental Health Department, notes: “There is no mental health ‘system’ in Michigan… We have a disjointed collection of too few state hospitals, private hospitals that are seeking to profit off public patients… and too little state and community resources aimed at developing community-based programs.” (28)

County jails, an overlooked component of today’s highly profitable, highly racist prison industrial complex, incarcerate mentally ill and poor Black people at alarming rates. In recent history, Wayne County had planned to build a $533 million dollar jail to house 2280 adults and 160 youth—even though the entire county has a maximum population of 1700 prisoners daily, which has been decreasing over the past 12 years. (29) Beds in these jails are constructed for Black people, seeing that they make up 70% of the jail population in the county (Figure 3). (30) Prioritizing jails over mental health institutions increases the likelihood that a severely mentally ill person will be sent to jail, the least therapeutic environment. As Milton Mack, Probate Court Chief Judge, says, “We are now using jails and prisons as our de facto mental health system.” (31)

Poor people are kept imprisoned by the cash bail system. Nearly half a million people are currently being held in local jails solely because they cannot afford bail, accounting for 99% of jail growth. (32) 62% of people in Wayne County jails have not been convicted of a crime and are in pre-trial detention because they cannot post bail (Figure 3). (33) Because they cannot maintain their jobs and care for their families while sitting in jail, low-income people are systematically coerced into taking plea bargains, regardless of their guilt.

The judicial system contributes to this phenomenon: in Michigan, pleading insanity as a defense and being found not guilty due to insanity is only granted 7% of the time. (35) This is partly because juries think defendants use “insanity” as an easy way out of justice. The MDOC instead created the Rehabilitation Treatment Services (RTS) program, which provides in-patient mental healthcare, ironically, within prisons. (36) This means the system punishes people for being mentally ill.

Re-Entry

Being released from prison comes with numerous restrictions, which increases the likelihood of reoffending and initiates reentry into the prison system. For example, mandatory background checks and “The Box”—a question commonly included on job applications that requires the disclosure of criminal history—halt reintegration and prevent formerly incarcerated people from gaining employment and accessing upward mobility. The Box serves no purpose other than to stigmatize incarceration and feed more prisoners back into the system for the benefit of corporations profiting off of the slave labor. The majority of those caught by the system are Black people, the same people availed the least opportunities in the job market.

Part III: Community-Led Initiatives

“When Black lives matter, everybody’s life matters, including every single person that enters this criminal justice system, and this prison industrial complex. It’s not just even only about Black lives—it’s about changing the way this country understands human dignity.” (38)

– Van Jones, 13th

(37) The capacity of Detroit community members to mobilize themselves continues to play an important role in addressing issues neglected by governments. This is especially important when it comes to policing. The list of organizations discussed is not exhaustive and does not capture the crucial, but less visible, work being done by families and neighborhoods.

Detroit is, according to longtime community activist Ron Scott, home to the Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality, one of the foremost organizations addressing the pervasive problem of police brutality in the U.S. (39) It aims to enhance communities’ capacity to document and expose police violence, as well as strengthen grassroots responses to conflict through peer mediation and restorative justice. (40)

The existing network of support organizations for families affected by mass incarceration must be highlighted.

Services are also available once citizens enter the legal system. The Detroit Justice Center provides free community legal services based on referrals from long standing local organizations. The DJC partners with The Bail Project, recently arrived from the Bronx, which funds bails up to $5,000 and provides reminders for the court appointment, as well as transportation and childcare when needed.

The existing network of support organizations for families affected by mass incarceration must be highlighted. This includes groups of mothers (Mothers of Incarcerated Sons Society/M.O.I.S.T) as well as support groups for families in general (groups at the Hope Community Church, Hope 4 Healing Hearts, the Detroit Parent Network with its “Beyond the Bars” program).

Once a Detroiter is released from imprisonment, various support services are available. The state and city provide access to training and other employment-related services before and after release through the Michigan Prisoner Re-entry Program and the Detroit Employment Solutions Corporation. However, these institutions are complemented by community initiatives like Man Power Mentoring Inc. which offers parolees or individuals in the MPRI program a mentor to help them through re-entry. The Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation provides the Reentry Services Case Management program and free tattoo removal. Cass Community Social Services acts on another scale, helping re-entering people access food, jobs, and housing. (41)

Often forgotten when discussing policing is the role of organizations helping with physical and mental health issues in order to promote successful reintegration and, consequently, low reoffending rates. Central City Integrated Health offers community re-entry services such as mental health care, substance disorder treatment, employment and housing services, among other social services. Organizations including Abundant Community Recovery Services Inc. and Hope not Handcuffs provide assistance to people struggling with opioid addiction and related challenges experienced by families.

Part IV: Technological Advancement

“Systems of oppression are durable, and they tend to reinvent themselves.” (42)

– Glenn Martin, 13th

In July 1967, military tanks rolled down the streets of Detroit. Wartime technology, rather than conflict resolution measures, were used to silence and criminalize Black Detroiters involved in the Rebellion. Since then, American police departments have become increasingly militarized and, at the same time, technologically advanced. (43) While this may have had benefits for individual officers and departments, the public has not experienced a comparable increase in police accountability or community control. A discussion of a more equitable future, especially for marginalized communities, must therefore address this critical gap.

The debate on police body-worn cameras (BWCs) often uplifts this technology as a key solution for police brutality. However, video footage has failed to assist victims to convict police officers in numerous trials, most notoriously in the shooting of Philando Castile in 2016. (44) Therefore, it is necessary to reevaluate the present and potential impact of this technology. Procedurally just practices promoted by BWCs, not BWCs alone, can increase citizen satisfaction and safety in police interactions. According to a study, officers with BWCs made slightly fewer arrests. The “civilizing effect” produced by BWCs included decreased use of force and complaints against officers. (45) However, these effects only occur when police officers cooperated with additional policies mandating when officers activate BWCs rather than relying on officer discretion. In fact, when departments did not clearly enforce these policies, use-of-force incidents increased. (46) In order for BWCs to effectively enforce police accountability, they must be implemented in a way that regulates officer behavior.

The massive amount of data produced by these and other emerging technologies poses a challenge for police departments, which generally do not have the capacity to store it.

Community Control and Data Justice

Conversations regarding BWCs and other technologies must also recognize that it is not only police being recorded, but also community members. The Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality and the Detroit Community Technology Project have outlined demands for widespread data accessibility for citizens, journalists, and researchers alike. Concerning BWCs and other recording technologies, community members must have a say in which data is saved, where data is stored, and how long it is stored for. The massive amount of data produced by these and other emerging technologies poses a challenge for police departments, which generally do not have the capacity to store it. This creates a market for private management of sensitive public information. (47) Opportunities for profit and inequitable surveillance must be combatted primarily via community ownership and decision-making.

Part V: Recommendations

“We got to ask ourselves, ‘Do we feel comfortable with people taking the lead of a conversation, in a moment where it feels right politically?’ Historically, when one looks at efforts to create reforms, they inevitably lead to more repression.” (48)

– Cory Greene, 13th

Policy Change

(49) Given the economic and racist (read: white supremacist) interests invested in preserving the carceral state, change is difficult and reforms are often incomplete. For total reform, we believe it is crucial to uplift the voices of those directly impacted by the rigged criminal justice system. Tied specifically to our above analyses, we propose the following recommendations to ALL stakeholders:

- Inspired by the Movement for Black Lives platform, communities must gain control of law enforcement agencies.50 Civilian oversight of hiring, firing, and general policy is necessary.

- Abolish cash bail and provide services—for example, reminders, transport, and childcare—to help people attend their arraignment hearings. By ending cash bail, poor people and people of color will be less likely to be detained and systematically coerced to plead guilty.

- Introduce a comprehensive forensic psychiatry system such as the model South Africa has adopted.

- Require jury education on the insanity defense. Ensure that jurors fully understand the meaning of a “not guilty” verdict under the varying circumstances in which mental illness plays a role in criminal cases.

Rethinking ‘Justice’

Policy change can only go so far in a society that values punishment over restoration. Total reform requires a shift in how the nation collectively understands justice.

- Protect the criminal justice system from capitalist interests, ensuring that no company, politician, or organization profits off of incarceration. This means paying incarcerated people a fair wage, providing them with publicly funded health and social services, and abolishing for-profit prisons and prison service contracts.

- Destigmatize experiences of incarceration. With regards to the box debate, stigma persists even if ‘The Box’ does not exist. Prior interactions with the criminal justice system should never disqualify applicants from accessing jobs, housing, and social services.

- Invest in restorative justice. Potential improvements include: replacing correctional officers with trained social workers, increasing opportunities for education and creative expression, and exploring mediation, rehabilitative programs, and other anti- carceral models of justice.

- Approach all criminal justice conversations—whether about policy- creation, journalistic reporting, or academic research—from an intersectional lens. This means highlighting the impact of incarceration on Black women, trans and gender non-conforming people, poor people, people of color, undocumented people and those with mental illness. We attempted applying this very lens, yet consistently focused on Black men, maintaining the discursive status quo.

- Provide spaces for community healing. Communities need to be involved in the reintegration process, as crime destabilizes communities. This destabilization can be remedied through community counseling, mediation services, and education on how incarceration can impact those who go through the system. This will destigmatize those returning from prison and begin mending any bonds broken before or through incarceration.

References

- DuVernay, Ava, dir. 2016. 13th. Netflix.

- Kerner Commission Report. 1968. Kerner Commission Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Publishing Office. www.eisenhowerfoundation.org/docs/ kerner.pdf.

- Stateside Staff, and Jamon Jordan. 2017. “How the Roots of Detroit’s Police Department Helped Spawn 1967 Rebellion.” Michigan Radio. National Public Radio. July 20. www.michiganradio.org/post/how-roots-detroits-police-department- helped-spawn-1967-rebellion.

- After ‘67, Big Four units reincarnated as S.T.R.E.S.S (Stop The Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), killing 22 Detroiters in two and a half years. Binelli, Mark. 2017. “The Fire Last Time.” The New Republic. April 6. https://newrepublic.com/article/ 141701/fire-last-time-detroit-stress-police-squad-terrorized-black-community.

- McGraw, Bill. 2017. “In a City with Long Memories of Racial Torment, Detroit’s Police Chief Seeks to Turn a Corner.” Detroit Journalism Cooperative. Bridge Magazine. February 20. www.detroitjournalism.org/2016/04/20/in-a-city-with- long-memories-of-racial-torment-detroits-police-chief-seeks-to-turn-a-corner/.

- Edison, Jeffrey. “The Legacy of Policing in Detroit.” Lecture presented to Humanity in Action fellows, Detroit, MI, July 2018.

- Stateside Staff, “Roots of Detroit’s Police Department.”

- Ibid.

- McGraw, “Detroit’s Police Chief Seeks to Turn a Corner.”

- Ibid.

- Thompson, Heather Ann. 2014. “Unmaking the Motor City in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” Journal of Law and Society, 45-46. drive.google.com/file/d/ 0B_PtL2SbGjSCcXV5SlZJMTdsMGs/view.

- Ibid, 46.

- Ibid.

- Thompson, Heather Ann. “1967: The Detroit Rebellion.” Lecture presented to Humanity in Action Fellows, Detroit, MI, July 2018.

- Thompson, “Unmaking the Motor City,” 53.

- Wagner, Peter, and Wendy Sawyer. 2018. “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2018: Michigan Profile.” Prison Policy Initiative. March 14. www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/ MI.html

- Wagner, Peter, Aleks Kajstura, Elena Lavarreda, Christian de Ocejo, and Sheila Vennell O’Rourke. 2010. “Fixing Prison-Based Gerrymandering after the 2010 Census: Michigan.” Prison Gerrymandering Project. Prison Policy Initiative. March. www.prisonersofthecensus.org/50states/MI.html.

- McGraw, Bill. 2017. “The War on Crime, Not Crime Itself, Fueled Detroit’s Post-1967 Decline.” Detroit Journalism Cooperative. Bridge Magazine. February 20. www.detroitjournalism.org/2016/10/24/the-war-on-crime-not-crime-itself-fueled- detroits-post-1967-decline/

- DuVernay, Ava, dir. 2016. 13th. Netflix.

- Gúzman, Martina. “Disparities in Justice, Health and Opportunity for Detroit’s Brown Communities.” Discussion with Humanity in Action Fellows, Detroit, MI, July 2018.

- Ashenfelter, David, and Joe Swickard. 2000. “Detroit Cops Are Deadliest in U.S.” The Police Policy Studies Council. May 15. www.theppsc.org/Archives/DF_Articles/ Files/Michigan/Detroit/FreePress052000.htm.

- Bates, Timothy. 2010. “Driving While Black In Suburban Detroit.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 7 (01): 135. drive.google.com/file/d/ 0B_PtL2SbGjSCUEpHTm9paEVHMU0/view

- Gerber, Elisabeth, Jeffrey Morenoff, and Conan Smith. 2017. “Detroit Metropolitan Area Communities Study.” Rep. Detroit Metropolitan Area Communities Study.

https://poverty.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/55/2018/04/winter-2017-

summary-report-final.pdf. - Ibid.

- Lessenberry, Jack. 2018. “Michigan’s Mental Health Scandal.” Detroit Metro Times. Detroit Metro Times. March 7. www.metrotimes.com/detroit/michigans-mental- health-scandal/Content?oid=9900977.

- Doherty, Matthew. 2015. “Incarceration and Homelessness: Breaking the Cycle.” COPS Community Policing Dispatch. US Department of Justice. December. cops.usdoj.gov/html/dispatch/12-2015/incarceration_and_homelessness.asp.

- Ibid.

- Lessenberry, “Michigan’s Mental Health Scandal”.

- “New Wayne County Jail Fact Sheet.” n.d. Rep. New Wayne County Jail Fact Sheet. Detroit Justice Center. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/ 5a413ae949fc2b12a2cb973f/t/5b3a20cef950b774336a7f7a/1530536142781/Fact Sheet 6.29 (1).pdf.

- Ibid.

- Lessenberry, “Michigan’s Mental Health Scandal”

- “Why Bail?” 2018. The Bail Project. https://bailproject.org/why-bail/.

- “New Wayne County Jail Fact Sheet,” Detroit Justice Center.

- Ibid.

- Hilf & Hilf. “Michigan Insanity Defense – Not Guilty By Reason of Insanity and Guilty but Mentally Ill.” Michigan Criminal Attorneys Blog. August 07, 2017. https:// www.michigancriminalattorneysblog.com/michigan-insanity-defense-not-guilty- reason-insanity-guilty-mentally-ill/.

- “Rehabilitative Treatment Services.” 2018. Michigan Department of Corrections. MDOC. www.michigan.gov/corrections/0,4551,7-119-68854_68856_9744-23257–, 00.html.

- We gathered information for this section from in-person interviews and organization websites. See “Research Notes” for more information.

- DuVernay, 13th. Netflix.

- Petty, Tawana “Honeycomb.” 2015. “Police Brutality, Detroit and the History of Organized Intervention,” Black Bottom Archive. October 27. http:// www.blackbottomarchives.com/allaboutdetroit/police-brutality-detroit-and-the- history-of-organized-intervention.

- Williams, Candice. 2017. “Anti-violence Group Plans Detroit ‘Peace Zone’.” The Detroit News. January 03. https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit- city/2017/01/03/anti-violence-group-plans-detroit-peace-zone/96135214/ .

- Fowler, Rev. Faith. “Cass Community Services.” Discussion with Humanity in Action Fellows, Detroit, MI, July 2018.

- DuVernay, 13th. Netflix.

- War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Police.” 2004. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/report/war-comes-home- excessive-militarization-american-police.

- Lopez, German. 2017. “The Failure of Police Body Cameras.” Vox. July 21. www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/7/21/15983842/police-body-cameras- failures.

- Golian, Laura, Mathew Lynch, Nancy La Vigne, Dave McClure, Daniel Lawrence, and Aili Malm. 2017. “How Body Cameras Affect Community Members’ Perceptions of Police.” Rep. Urban Institute, 8. www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/ 91331/2001307-how-body-cameras-affect-community-members-perceptions-of- police_1.pdf.

- Ibid, 6.

- Joh, Elizabeth E. 2016. “Beyond Surveillance: Data Control and Body Cameras.”

Surveillance & Society 14 (1): 134–35.

Research Note

Abundant Community Recovery Services Inc.: https://www.abundantcommunityrecovery.com/

CASS Community Social Services: https://casscommunity.org/

Central City Integrated Health: http://www.centralcityhealth.com/diversion-recovery- reentry/

Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality: http://www.detroitcoalition.org./

Detroit Community Technology Project: https://www.alliedmedia.org/dctp/datajustice

Detroit Employment Solutions Corporation: https://www.descmiworks.com/ returningcitizensproject/

Detroit Justice Center: https://www.detroitjustice.org/

Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation: http://www.dhdc1.org/

Detroit Peace Zone: https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/ 2017/01/03/anti-violence-group-plans-detroit-peace-zone/96135214/

Hope Not Handcuffs: https://www.familiesagainstnarcotics.org/hopenothandcuffs Man Power Mentoring: https://manpowermentoirng.webs.com/

Michigan Prison Reentry Program: https://www.bhpi.org/?id=54&sid=1

Parolee Resources: http://julieslist.homestead.com/paroleeprograms.html Prisoner Advocacy: http://www.prisoneradvocacy.org/resources/support-groups/ The Bail Project: https://bailproject.org/